Loeb and Loeb Law Firm

Pioneer Los Angeles Law Firm 1909 - Present

Joseph (1883-1974) and Edwin Loeb (1886-1970) in 1913

The Loeb and Loeb law firm is one of the oldest and most prestigious firms in Los Angeles. It was founded in downtown Los Angeles in 1909 and now has offices in downtown Los Angeles, Century City, New York, and Nashville. Its move from downtown LA to Century City mirrors the movement of the old-time Jewish and Gentile communities, as well as the members of my family.

The founding partners Edwin and Joseph Loeb were the grandsons of the noted pioneer businessman, real estate magnet, historian Harris Newmark who was the author of “My Sixty Years in Southern California 1853-1916.” Harris Newmark was my great great Grandfather and Edwin and Joe Loeb were my great Uncles the younger brothers of my Grandmother Rose Loeb Levi (Schatzie.)

The following pages will be a Personal Family History followed by an Oral History of Joseph Loeb conducted by Claremont Colleges, Membership and Activities of Edwin and Joe Loeb, with Selected Poetry by Joe Loeb, and a Short History of Loeb and Loeb.

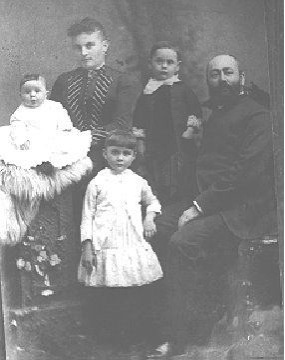

The Leon Loeb family – 1886- Lt. to Rt. Edwin Loeb (baby), Estelle Newmark Loeb (25 yrs.), Joseph Loeb (6yrs.), Leon Loeb (41 yrs.), Rose Loeb (5yrs.)

I. Personal History

On Tues. nights my Grandparents would have the family and assorted friends for dinner and it would be great fun. There would usually be 12 or 14 people, not 13 as my Dad was superstitious. The food was delicious, cooked by varies cooks and served always by Elsie who over the years performed the same duties at my parents’ parties. The dinners were lively and verbal as the families were Franco-German, very intelligent and very argumentative. Uncle Joe and his wife Amy and Uncle Edwin were sometimes there and as far as I remember I only saw them there. They were a generation older than my parents and they didn’t really socialize with each other. I don’t remember either of them coming to dinner at our house. They had 4 daughters between them but the only one I recall meeting there was Edwin’s daughter Margie. She usually came with Edwin. She was very small, probably 4”6 or so, after all Edwin was about 5’4’’. That led some of the Loeb and Loeb attorneys in oral interviews to imply that she was mentally disabled/retarded and this was a tragedy in his life. On the contrary Margie was very normal and highly intelligent. She was a Stanford University graduate in the early 1930s and was part of the original Stanford-Binet IQ test that followed the high IQ participants for a period of time. What I didn’t realize probably because of her small stature was that she was close to my Mother’s age. I always thought that she was only around 10 yrs.older than I, but she passed away last year in Santa Monica, CA at 89.

Every thing I’ve read about Edwin, Joe and most of the male family members state that they played cards all the time. But that never happened at my grandparents’ dinners. It was strictly conversation.

From what I observed, and I worked one summer at Loeb and Loeb when I was a UCLA undergraduate, and from what I’ve read, Edwin and Joe were both remarkable human beings but had totally opposite personalities and also completely different interests in Law.

Uncle Edwin was really funny. He was average looking and was short, but had an incredible magnetic personality, He was lively and charismatic, and he had the ability to really attract others. Everybody loved him. Because he was irresistible he brought a lot of business into the firm. It was he, thru his friendships, (and card playing), who was responsible for all the studio business. Starting around 1914 Loeb and Loeb represented Carl Laemmle (Universal), Sam Goldwyn (Sam Goldwyn Productions), Louie B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg (MGM which Edwin helped to set up), Mary Pickford, Douglass Fairbanks, D.W. Griffin, and Charlie Chaplin (United Artists), the Schenck Bros, (Twentieth Century Fox) and the Warners (Warner Bros). Many of these men eg. Laemmle, Goldwyn, Thalberg and Mayer were his very close and sometime card-playing friends. In fact when Thalberg first came to LA he moved into Edwin’s house and until his death in 1938 at 39 he was Edwin’s best friend. In 1924 Edwin helped set up MGM and in 1927 was a founder and the legal organizer of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. It is believed the idea of having the Academy and the Academy Awards was his. My Mother and Father went with Edwin, Irving Thalberg and Norma Shearer to the first academy awards in 1928 at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel where some years later Edwin lived.

Some of The Founders of the Academy 1927

Edwin Loeb is in back row with red. Seated: on left Louis B. Mayer, Conrad Nagel, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and 2nd rt. Joseph Schenck

Program for Seventy Fifth Anniversary of The Academy Awards 2002

Unknown Affair-Perhaps MGM personnel or executives - before 1938. Standing in back of table: L.B. Mayer in middle, perhaps Sam Goldwyn to our left. Irving Thalberg is extreme left in white suit, and Edwin is seated back left in front of Thalberg.

I also heard the “Thalberg Story” that Edwin got him his first job with Carl Laemmle and he did well there, but Rosabelle Laemmle the daughter of Carl Laemmle fell in love with him and as a result he felt uncomfortable and wanted to leave. So, Edwin arranged for him to leave and join with Mayer at MGM. I knew Rosabelle because my parents were friendly with her and her husband Dr.Stanley Bergeman, and their daughter Carole was an acquaintance of mine. But, I didn’t really know the Laemmle connection till I was older. Although Uncle Edwin was married three times, I only knew his third wife Cally. She was supposed to be bawdy and have a “foul” mouth, but when I met her she was lovely, attractive and couldn’t have been nicer.

Edwin was a great storyteller but I only remember one, which he probably told me because I was a young child. One night after dinner he told me that he had met Joel Kupperman the young math genius who was on the “Quiz Kid” radio show in the 1940s and fifties. He told Joel that he had a difficult math problem for him. “If you have a conical hole 10 ft. wide by 15 ft. long by 10 ft. deep how much dirt will there be?” He said Joel didn’t get the right answer, can you?

I really love films, and during the late 1950s Edwin was kind enough to arrange for me to go to the Academy screenings and take a friend, fellow artist Norman Holden. I had no idea at the time of his connection to the Academy.

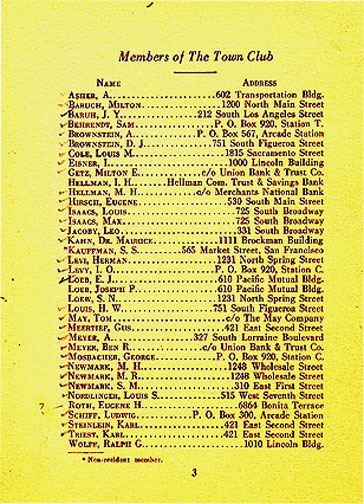

Title cover of The Town Club a downtown social-business club that Joe and Edwin were members of.

The Town Club 1922 – members were Prominent Jews in Los Angeles- Edwin and Joe Loeb, My Grandfather Herman Levi, and other relatives. I don’t have a list, but I imagine that all these men were the first members of Hillcrest Country Club founded 1922. A Loeb relative S. (Sam) M. Newmark was the first president of Hillcrest.

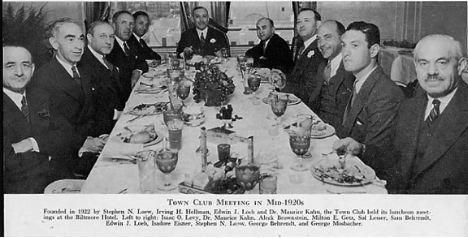

Town Club Meeting Mid-1920s

Edwin Loeb right back, other relatives are Steve Loew (Capital Milling Co.) Sr, rt. 3rd from front, and Milton Getz (Union Bank) lt.4thfront

Uncle Joe was completely different than Edwin. I remember him as being formal and gentlemanly and a lovely pleasant looking man. He was careful, serious and fastidious, but yet a creative business attorney. He had a reputation of being the finest business lawyer in Los Angeles. Apparently, he kept a precise record of everything he did and would describe every conversation in lengthy timesheets. After every phone call he would dictate a memo of the call into a Dictaphone, and then that would be transcribed. At the University of California (Phi Beta Kappa) he was editor of The Daily Californian and his legal papers were written in simple clear language that was easy to follow. He wrote poetry some of which are included in his Oral Interview, and apparently his personal letters were written in poetic form. Ironically, even though Edwin seemed the more amusing, Joe’s poetry is very clever and witty reminiscent of Ogden Nash. He watched over the major business, corporate accounts, particularly, the ones that were family, Union Bank and Cedars of Lebanon Hospital. His main client was Union Bank where he was also a director. Joe was very active in Republican politics, and his good friend Earl Warren then governor of California appointed him to the California State Board of Education. His charitable, political, and educational activities were extensive and included: Board of Fellows of Claremont University Center, President of Hillcrest Country Club: 1933-1937, Board of Directors of Los Angeles County Bar Association: 1915-1922, President of United Jewish Welfare Fund: 1937; and General Campaign Chairman: 1938, Founder, Director and First President of Southern California Chapter of the Arthritis Foundation, Director of Jewish Orphan’s Home of Southern California (now called Vista Del Mar Child Care Service): 1916-1939; from 1920-1926 he was its President, and Board of Governors, Los Angeles Civic Light Opera Association.

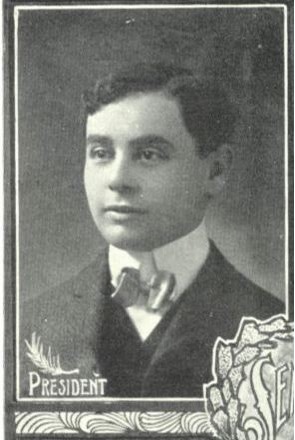

Joseph Loeb at 18 in 1901, a leader at Los Angeles High School. There were 75 students in his class. Most of the members of the Harris Newmark family went and would go to Los Angeles High School through the 5th generation (1960s).

Uncle Joe because he was on the State Board of Education apparently knew a lot of prominent educators. When I went to UC Berkeley in 1953, Joe, one night at my grandmothers, told me to look up his friend the President of the University Clark Kerr. I actually had an opportunity to do so as there was some kind of reception for freshmen to meet President Kerr. But I wasn’t in to that kind of thing then so I didn’t go. I was an idiot!

In 1960, I lived in New York City near Union Square on E.12st.in a small converted loft. Previously, I had never met Joe’s two daughters. However, his oldest daughter Kathleen was married to Ed Bernath and they resided in NYC. He was Assistant Superintendent of New York City Schools and she was taking classes at Columbia in librarianship. They lived close to Columbia around 116th and Riverside Dr. I saw them several times and they were lovely people and had a large 2 or 3 bedroom apartment. I wasn’t working that year as I had saved money from teaching and my parents were covering the rest, but the next year it would be necessary to find a part or full time job. Ed knew this and he got me an interview for an art position at Bronx Community College, and as I remember it went well. They also said that when they left New York that I could possibly have their rent control apartment. Neither the teaching job or the apartment ever came about as in mid summer I returned to LA.A few years later, I heard that he had to retire because of a bad back, they had moved to the LA area, and she was working as a librarian. I thought she would be at Claremont College, but recently I was told she was at The Huntington Library in San Marino, CA.

Joe really helped me out in 1962. I had received an MA from UCLA in painting, and was student teaching at Santa Monica College in the spring of 1962 in order to get a teaching credential at the end of the semester. SMC offered me a part-time teaching (4 classes) position that next fall, but they needed to know that I had the required credential. My classes were finished and I applied in May, but I knew, because of the bureaucracy, it could take several months and might be too late. Uncle Joe heard about the situation, and told me to attend the State Board of Education Meeting (he had been a member) held that month in downtown LA, wait until the conclusion of the meeting and look up a man named Eli Abramavich. I should tell him that I was Joe Loeb’s niece and the situation. I did as he said and a week later my credential came in the mail and I taught at SMC in the fall.

I mentioned that I had worked at Loeb and Loeb one summer when I was at UCLA. I can’t quite remember whether the year was 1954 or 1955, but it was an enjoyable experience. I was a girl Friday, sometimes I was a receptionist, but mostly filed and read Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. There must have been around 20 or so lawyers, and of course, I had no idea who was an associate or who was a partner. I was unaware of the hierarchy. But, I think I was aware of who the bosses were, Uncle Edwin, Uncle Joe and their two secretaries! There was a receptionist and a switchboard operator, and that seemed to be the most difficult job of all with all those cables. I don’t recall that the attorneys had individual secretaries, but I remember a typing pool with a lot of women pounding away. All the lawyers were men and all the drones were women. There were no paralegals, no office manager. Uncle Edwin ran the office and his secretary Irene Nelson was in charge. I lived in Westwood and the law firm was at 6th and Grand in the Pacific Mutual building. Sometimes my Dad took me to work on his way to Capital Milling Co., but mostly Frank Feder and Fred Nicholas gave me a ride to and from work. They were really nice to me as were all the lawyers. Amazingly, it’s been almost 50 years but when I read the reminiscences of a few of the older attorneys’, I remembered the names of everyone they mentioned and sometimes their faces; Herman Selvin who was considered a great attorney, and always in the library, Walter Hilborn who was very debonair, my sweet Uncle Louis Lissner arriving around 10:30, Uncle Edwin Loeb hustling around, Uncle Joe Loeb who looked like a college professor, Alden Pearce, looking like old Pasadena, Karl Levy, Allen Sussman, Harry Swerdlow, Saul Rittenberg, Donald Rosenfeld whose brother Robert was my doctor, Harry Keaton, Myron Slobodian, Maurice Benjarmin, Michael Cohen , shortish and the Police Commissioner, Al Rothman, and Dwight Stephenson.

From 1967 to 1982, Frank Keesling handled my income taxes, and he never made me feel unimportant. My primary income came from teaching and some art sales, but I was not making as much money as other members of my family. On the contrary, he treated me as if I were very important. I think right from the beginning he had me come at 11:00 and we’d do the taxes, and then he’d take me to lunch. I can’t remember the names of the restaurants but they were chophouses. Frank would have a martini (or two) and in the later years when the accountants joined us, Stanley Eisenberg etc., all of us would be talking and he would kind of nod off.

When he did my taxes, I would have a list of expenditures, expenses, deductions and I’d read them to him and he’d write them down, and I guess figure them out later. When I told other members of my family about the lunch, they said they never got treated so well. Plus, as I found out when I switched to a CPA, the fees at Loeb and Loeb were more reasonable (usually an hour) and I had to pay a lot more with not as good representation. Probably, because he was familiar with the tax laws, I also was able to take many more deductions.

Another very helpful and a really nice person was Marvin Greene. At different times I had some problems with art sales or damages to my artwork, and I would call Marv. He would either tell me what to do or write a letter for me. Either he didn’t charge me or if he did the fee was nominal. What I didn’t know and just found out was that he was the attorney for our family business the Capital Milling Co. So, that somewhat explains why he was so helpful.

One last comment, I always observed and read that the members of my family who were in business were always honorable. Starting with Harris Newmark and Kasper Cohn (who became a banker because people trusted him with their money), continuing with my grandfather Herman Levi, my uncle Leon Levi (with Loeb and Loeb), my father John Levi Sr. and my brother John Jr. Joe and Edwin Loeb were no exception. From what I know about them not only were they incredibly smart, but men of integrity who would prefer not to represent someone than to do something improper. I would hope that the lawyers who represent the 21st century version of Loeb and Loeb remain as ethical and principled, and share the same sense of dedication to their clients that Joe and Edwin had.

2. Oral History of Joseph P. Loeb taken by Claremont Graduate School, 1965

JOSEPH P. LOEB

Los Angeles Attorney

Oral History Program

Claremont Graduate School

Claremont, California

1965

[Edited by William B. Colitre, J.D. Loeb&Loeb LLP, 2002 and Linda Levi, MA. 2003]

This manuscript is the result of a tape-recorded interview conducted with Joseph P. Loeb by Enid H. Douglass and David W. Davies on behalf of the Claremont Graduate School Oral History Program on February 19, 1965, at Alta Loma, California.

Joseph P. Loeb has read the interview transcript and made only minor emendations. The reader should bear in mind, therefore, that he is reading a transcription of the spoken, rather than the written, word.

INTERVIEW HISTORY

INTERVIEWEE:

Joseph P. Loeb

INTERVIEW TIME AND PLACE:

February 19, 1965

Mr. Loeb’s ranch in Alta Loma, California

Mrs. Loeb (Amy Kahn) also present

INTERVIEWERS:

David W. Davies

Librarian, Honnold Library

Claremont Colleges

B.A., University of California, Los Angeles [English and History]

M.S., University of California, Berkeley [History]

Ph.D., University of Chicago [Library Science]

Enid H. Douglass

Associate Director, Oral History Program, Claremont Graduate School

B.A., Pomona College [Government]

M.A., Claremont Graduate School [Government]

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

Joseph Loeb was born in Los Angeles on December 11, 1883. His parents were Leon and Estelle (Newmark) Loeb. Leon Loeb arrived in Los Angeles in 1864 from France, and, in 1884, he succeeded Eugene Meyer as French Consular Agent. Estelle Newmark was the daughter of Sarah and Harris Newmark. Harris Newmark was the author of a well-known book on the history of Southern California, Sixty Years in Southern California 1853-1913.

Mr. Loeb attended the Los Angeles public schools and graduated from Los Angeles High School. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of California at Berkeley, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in 1905. He then worked as an office boy in the law offices of Henry O’Melveny. In 1906, he was admitted to the bar in Los Angeles and retained his association with the O’Melveny firm until 1907. At that time, he joined Edward G. Kuster in the practice of law; and, in 1908, they, along with Edwin J. Loeb (brother of Joseph Loeb), formed the law firm of Kuster, Loeb and Loeb. Edwin and Joseph Loeb read proof for their grandfather, Harris Newmark, at the time of the publication of his book on Southern California.

About 1911, Edward Kuster left the law office, and the firm of Loeb and Loeb was established. Over the years, the firm has operated under various names: Lowenthal, Loeb and Walker; Loeb, Walker and Loeb, to the current name, Loeb and Loeb. Through a coincidence, the firm began handling legal matters related to the movie business. This resulted in a substantial practice in connection with the movie industry, including legal service to Carl Laemmle, Universal Studios, Metro Goldwyn Mayer, Samuel Goldwyn, and United Artists.

In 1943, Joseph Loeb was appointed by Governor Earl Warren to serve as a member of the California State Board of Education, in which capacity he served until 1956. From 1947 until 1972, he was a member of the Board of Fellows of Claremont Graduate School and University Center. He was a member of the Los Angeles County Bar Association, which awarded him a fifty-year membership certificate in 1966.

Mr. Loeb married Amy Cordelia Kahn (1885-1967) of San Francisco on January 24, 1909. They were the parents of two daughters: Kathleen (Mrs. Edward J. Bernath), born November 11, 1910; and Margaret (Mrs. Edward J. Soares), born June 10, 1913. Mr. Loeb retired from law practice in June of 1965. He died on July 18, 1974.

INTERVIEW

FAMILY BACKGROUND

DAVIES: I would like to hear about your own father?

LOEB: He came from Alsace. He came to Los Angeles in 1864.

DAVIES: Did he go into business here in 1864?

LOEB: I wasn’t here then, but there is something about him in those newspaper clippings I was showing you and something about him in Sixty Years in Southern California. He was in the City of Paris, a dry goods store on the west side of Spring Street in Los Angeles. I imagine that the site is now covered by the City Hall. A part of the street isn’t there anymore.

DOUGLASS: What was his name?

LOEB: His name was Leopold before he came over here, but he called himself Leo, or Leon.

DAVIES: Didn’t you say that at that time you lived in a house on Grand Avenue, across from the Biltmore-Pacific Mutual Building?

LOEB: I was born on the east side of Hill Street, between Second and Third Streets. My grandparents, the Harris Newmarks, lived on the west side of Fort Street, immediately in back of our home. And then, some time when I was about three years old, or a little less, we moved to 647 South Grand Avenue.

DAVIES: Didn’t you say that all of that street had houses with picket fences at one time?

LOEB: Not all of them, because the corner of Grand Avenue and Seventh was, as we used to call it, an empty lot. In other words, it was unimproved. Marco Newmark and I used to play Indian in the weeds there, right at the corner of Seventh and Grand Avenue. Then, our house was next, and there were houses from there up to the corner of Sixth Street. At Sixth Street, there was a grocery store owned by a man named Wallace. It was on the southwest corner of Sixth and Grand Avenue.

DAVIES: When your father had the City of Paris, did you work in it?

LOEB: No. I was only a kid. The only thing I remember about the City of Paris is sitting on top of one of the counters and being given beads or something with which to play.

DAVIES: Can you remember Harris Newmark’s store?

LOEB: No. By the time I knew my grandfather, the company was M. A. Newmark & Company, wholesale groceries. M. A. Newmark was Morris A. Newmark, a nephew of Harris Newmark, and his wife was a sister of Dr. Leo Newmark. Marco Newmark was Harris Newmark’s son and my uncle. Marco was my mother’s brother, and he was only five years older than I was. We grew up together. My grandfather, Harris Newmark, lived for several years after I was married. He died on April 4, 1916.

DOUGLASS: What did your father do after he had the City of Paris store?

LOEB: I am a little hazy about what he did. I remember that he had an office on the west side of Spring Street, north of Temple Street. Then he went into the business of hides and pelts with my grandfather.

DAVIES: You told me that Kaspare Cohn got into the banking business from lending money to Basque sheepherders.

LOEB: You see, in the early days there were certain people, particularly the Basques, the oldtimers, but also a lot of others like the Dominguez family and the De Francis family, who did not trust bankers. But they trusted Kaspare Cohn. So, in spite of the fact that he was a wool merchant, they used to deposit money with him. He paid them interest. I don’t remember what rate it was, but it was much bigger than the banks pay now. They were allowed to check it out from time to time. I think he gave them printed forms of checks, at least he did in later years. If they needed some of their money, they just drew a check.

Then Kaspare Cohn’s two daughters married. His eldest daughter, Rachel, married Ben R. Meyer.*

LOEB: His younger daughter, Estelle, married Milton Getz.* They went into the business with my cousin, Kaspare Cohn, and he wanted them to have an interest in the business. So he came to me, curiously enough, and had me form a corporation, just an ordinary business corporation. And one day the Superintendent of Banks walked into his office and said, “Mr. Cohn, you are doing a banking business.” If you are a corporation doing a banking business you have to conform to the banking laws and qualify as a bank.

So they went to Henry O’Melveny then, because he represented most of the people who had the big deposits with them. He formed a commercial bank, the Kaspare Cohn Commercial Trust and Savings Bank. Then when World War I started, the Bank of Italy changed its name to the Bank of America, and the Kaspare Cohn Commercial Trust and Savings Bank changed its name to the Union Bank. Then much later, they established a trust department and changed the name to the Union Bank & Trust Company of Los Angeles. The Superintendent of Banks would not let them call themselves the Union Bank & Trust Company because of a conflict of names with a concern in San Francisco. But the original name was Kaspare Cohn Bank.

DAVIES: Do you know anything about the new building at Wilshire and Western?

LOEB: That was built by George Getty or his oil company. He is the father of George Getty, Jr., who lives in Los Angeles and is said to be one of the richest men in the world. George Getty, Jr. is the president of the Los Angeles Club. The Los Angeles Club really grew out of the bank in an accidental way, because Harry Volk, then the president of Union Bank, thought that it would be a good idea to have a first-class restaurant at the top of the building. Of course, he had visited many banks over the country, and many of them had restaurants or clubs where the bank officers, the bank presidents in particular, would entertain V.I.P.s as they dropped into town. So the building was built with the idea of renting the upper floor to a restaurant. Then they couldn’t find anybody who would meet the requirements necessary to establish and operate a high-grade restaurant. So the Los Angeles Club, a non-profit, social membership club, was organized and is now located on the twenty-second floor of the building.

DAVIES: Now your father was Consul-General?

LOEB: They used to say he was the French Consul, but I think that technically he was the Agent Consulaire, either the second or third one here in Los Angeles. He succeeded another cousin of mine, Eugene Meyer, Sr. When Eugene Meyer moved to San Francisco in 1884, my father succeeded him as the French Consular Agent and served for more than fifteen years.

DAVIES: Was the French Hospital built in your father’s time?

LOEB: Oh, yes. He was on its board. I remember being taken there to visit, not for treatment.

DAVIES: Didn’t you tell me that at the time of the Franco-Prussian War he was not an American citizen and got into some sort of difficulty?

LOEB: Yes. He was living here in Los Angeles. His family was Alsatian French. When the Germans took over Alsace, the people who remained in Alsace had to take the oath of allegiance to Germany. Our whole family wouldn’t do it, and they moved into France. My father, as I said, came to Los Angeles in 1864, and so was here during the war. When it began to become clear from the news received here that his native city of Strasbourg (he was born in a suburb of Strasbourg) might be captured by the Germans, he rushed up to the federal judge and said, “I do not want to have to say that I was a German even for twenty-four hours, so please give me my citizenship papers now.” Whatever the laws were then, he was granted his citizenship and never was a German.

LEGAL TRAINING

DAVIES: Tell us about your education.

LOEB: I was going to be an electrical engineer. This amuses me because it shows how clearly I was really cut out to be a lawyer. I wanted to be an electrical engineer. Marco Newmark, my uncle, who was five years older than I was, and I had always been very chummy. We spent a lot of time together when he and his parents lived at Eleventh and Grand Avenue and we lived on Grand Avenue between Sixth and Seventh. I would go down to Grandma’s house to study with Marco and maybe even sleep there. Then, as we grew older, Marco went to the University of California at Berkeley, and I went to the old Los Angeles High School.

Marco came home from Berkeley one day, by which time his parents were living with us at Westlake Avenue between Eighth and Ninth, and Marco and I went to Westlake Park (now called McArthur Park) to pass the time. Marco said, “Wouldn’t it be a fine thing, Joe, if instead of being an electrical engineer, you would be a lawyer, because I’m going to be a lawyer, and we could be partners. And we would go through life together as we have grown up together.” So I said, “All right. I’ll be a lawyer. “But,” he said, “you’ll have to have an A.B. instead of a B.S. degree, and to have that, you will have to have a certain amount of Latin and Greek.” I had to re-arrange my high school course a little bit to take enough Latin to qualify me for entrance into the right department at Berkeley.

In Berkeley, a few of us who had to make up for our complete lack of knowledge of Greek joined a class under John Fleming Wilson (if I remember his name correctly), a man who had graduated from an eastern college and was at Berkeley working for either a master’s or a doctor’s degree. So I graduated from the university with an A.B. instead of a B.S. degree. I did not go to law school. I took the preliminary law courses as part of my A.B. degree, and then I decided I shouldn’t impose on my father by going to Harvard Law School, as I had intended, but go home for a year and work and then go to law school. Instead of this, I went into Henry O’Melveny’s office as an office boy and never did go to law school.

Coming back to Marco, who was to be my partner, my grandfather didn’t believe in professions at all. So shortly before Marco was to graduate, he received a telegram to hurry home as soon as he graduated because my grandfather had bought him a one-third interest in Lazarus and Melzer, a wholesale stationer business then on the east side of Los Angeles Street near Commercial Street. So poor Marco went into the wholesale stationery business, but he was so unhappy that after a year, my grandfather was persuaded to let him go back to college. By that time, Marco had come under the influence of Professor Morrison, a professor of philosophy at Berkeley, and had decided that he wanted to become a philosopher and a college teacher. He was going to Oxford. Why he ever thought he could get into Oxford, I don’t know. He tried Oxford unsuccessfully and then the University of Berlin. Then he came home and entered the wholesale grocery business with M. A. Newmark & Company. So he and I never did become law partners.

DOUGLASS: Did you go to Los Angeles High School for your college preparation?

LOEB: Yes.

DAVIES: How long were you with O’Melveny, Joe?

A. LOEB: And how well did you get paid?

LOEB: Well, in those days, it was a privilege to get into a law office. Some people made you pay for it. But I was admitted to the office without paying anything and, at first, without a salary. I used to do all kinds of errands. I remember one of the old ladies, Basque or Spanish, I forget which, came to see Mr. O’Melveny. He called me into his office. He was bursting with laughter. He said, “You take this watch to S. Nordlinger & Sons and have it repaired. This belongs to Mrs. So-and-So, an old client of the office. She doesn’t trust the jewelers, but she trusts me. So she brought this watch in so I could have it fixed.” So I took it to S. Nordlinger’s Jewelry Store and had it repaired. That’s the kind of preparation I had for the practice of law.

One day, I came into the place where my desk was, at the dead-end of the hallway, and there on the desk was a check for ten dollars, signed “H.W. O’Melveny,” payable to me. I went in and said, “Mr. O’Melveny, what am I to do with this?” I asked the question because I had picked up theater tickets for him and done all kinds of other errands and took it for granted that I was to be sent on another. “Why,” he said, “Joe, I don’t want you to work for me for nothing. I’m going to pay you ten dollars a month.”

DAVIES: How long did you stay there?

LOEB: I passed the state bar examination in 1906. I stayed with O’Melveny until the end of 1907.

DOUGLASS: Did this mean that you read law at night in order to prepare for the bar? Or did you have enough background between what you had at Berkeley and your experience in the law office?

LOEB: What I had at Berkeley wasn’t very helpful in a way, because it was only about one-third of a complete law course. But I had to study enough to pass the examination. The whole system was different then than it is now. The examinations were given by three judges of the District Court of Appeal. They were oral examinations. They lasted one day. One of the three judges was an ex-Confederate general, I think. He had gotten together a book of questions and answers. He was a great disciple of Herbert Spencer, and, as much as he could, he got into his questions and answers the philosophy of Herbert Spencer and at the same time the law.

Olin Welborn II had taken the examination six months before I was going to, and he had a copy of that book. He had typewritten the questions and answers. When he had passed his own examination, he handed those questions over to me, and two other fellows who were preparing the examination and I used to sit up nights and memorize those answers. Irving Walker was one of the men who worked with us. We took the examination at the same time. I can still see Irving sitting back in his chair with his right arm hooked over the back of it answering the one and only question that was put to him. There was a poor Negro boy who was the only one in the class who failed that day, although the examining judges did their best to help him out by hinting at the answers.

DOUGLASS: How big a group were sitting together taking the examination?

LOEB: I don’t remember--fifteen, twenty, thirty, fifty.

DAVIES: Who was in the O’Melveny office when you were there? Was Jackson Graves still there?

LOEB: No. There had been a firm of Graves, O’Melveny & Shankland. J. A. Graves became the vice-president in charge of the Farmer’s & Merchants National Bank when I. W. Hellman moved to San Francisco, and his brother, Herman Hellman, left the Farmer’s & Merchants Bank. Then Shankland and O’Melveny each formed his own firm. So when I went into O’Melveny’s office during 1906, he was the sole owner of the business. He had a very able trial lawyer with him, named Henry J. Stephens. Stephens had been the lawyer for the Santa Fe Railroad for a long time. I think he is the lawyer who handled the case whereby the Santa Fe Railway Company beat the government and established the title to the Bright Angel Trail in the Grand Canyon of the Colorado. Stephens was a really wonderful trial lawyer.

Then there was Edward G. Kuster, a nephew of William G. Kerckhoff. William Kerckhoff was one of the owners of the Kerckhoff Lumber Company, and he was associated with Allan C. Balch and some others who established the Pacific Light and Power Company. Ed Kuster had graduated from college shortly before I did and was going to law school. But he fell in love with one of the best-looking girls in my class, and he decided that without waiting until he finished his law course, he would take the bar examination and induce her to leave college at the end of her freshman year, so they could be married. So he had been practicing maybe two or three years when I came into the office. I used to call them my “ideal American couple,” if you remember. Later, she became the wife of Robinson Jeffers, the well-known American poet.

There was also, in the office, William White, who was the son of the late Senator Stephen M. White of California. Will, like me, was just a law student. Then there was Ralph Bandini, of the old Bandini family. All of these people were in the O’Melveny office. Will White, Ralph Bandini, and I ran errands. My brother, Edwin, came in later. As long as I was going to be a lawyer, he decided that he would be a lawyer. So he got a job there, and most of the time he ran the telephone switchboard and acted as receptionist.

DAVIES: O’Melveny had a lot of the early Mexican families for clients, didn’t he? Is that why he had Bandini in the office?

LOEB: Yes, so many of them. Incidentally, just to complete the description of his staff, he had two female stenographers, as we called them in those days. They were good, too.

IN PRACTICE AS KUSTER, LOEB AND LOEB

DAVIES: When did you decide to leave O’Melveny’s firm?

LOEB: Ed Kuster left the firm, and he tried to persuade me to leave with him. But I said that I couldn’t because I was just beginning. I had had no experience. I couldn’t establish my own practice that soon. He kept after me. He too had offices in the I. W. Hellman Building at Fourth and Main Streets, and took an extra room which he held in reserve while he was trying to persuade me to leave. After about a year, as I remember, he did finally talk me into it. And I went down there and practiced independently. We didn’t form a partnership until Edwin was admitted. Then we formed the partnership of Kuster, Loeb and Loeb.

DAVIES: How long did that last?

LOEB: Some years, believe it or not.

DOUGLASS: What year was the partnership of Kuster, Loeb and Loeb formed?

LOEB: It was in existence when we were married in 1909. So it was formed before then, and it lasted some time after that.

A. LOEB: You and Ed Kuster were busy with the switching case when we got married. It was an important case.

DAVIES: Tell us about the switching case.

LOEB: The Southern Pacific, the Santa Fe, and the Salt Lake Railway, all three of which served Los Angeles in those days, made a charge of $2.50 for every car that they spotted on an industrial spur. If the car was taken to the railroad’s own switching track and left there for the freight to be loaded or unloaded, that was that. But if the car was to be spotted on an industrial spur, like that of the Capitol Milling Company, for example, there was a charge of $2.50 a car. The only cities in the country in which that charge was made were Los Angeles and San Francisco.

There was an organization down here called the Associated Jobbers of the City of Los Angeles. A man named Fred P. Gregson was the Traffic Manager for this organization. There was a similar organization in San Francisco, and its lawyer was a man named Seth Mann. He, Ed Kuster, and I tried that switching case before the Interstate Commerce Commission (1910) and won the decision, knocking out the $2.50 a car charge.

DOUGLASS: I suppose that you were greatly appreciated for doing that?

LOEB: Yes. Ed and I, after considerable argument, persuaded the Associated Jobbers to pay us $25,000. I wish that we had been paid on the basis of the cars that were “spotted” on industrial spurs without a charge. Even twenty-five cents a car for the next twenty-five years would have given us a larger fee.

DOUGLASS: Did you make a case on the basis of discrimination within interstate commerce?

LOEB: No. It wasn’t that. It was a curious thing and completely accidental. I was up in the law library one day trying to find a theory on which to base our stand, and I ran across a series of English cases called the Railway and Canal Traffic Cases. I had never head of them before. Looking through those cases, I accidentally found that a rate for transportation is made up of a charge for taking on freight, for transporting the freight, and for unloading the freight. Therefore, to make an extra charge for unloading the freight is doubling up. We won the case on that theory.

DAVIES: Did Kuster, Loeb and Loeb have any more interesting cases?

LOEB: Yes. Ed and I, without Mr. Mann (who at that time was on the other side), won a case before the State Railroad Commission (now the Public Utilities Commission). We succeeded in convincing the Commission that there was unfair discrimination in the freight rates between San Francisco and the San Joaquin Valley points and between those same points and Los Angeles. We got much lower and fairer freight rates.

DOUGLASS: How did you happen to get this case and the switching case?

LOEB: My uncle, M. H. [Maurice. –Ed.] Newmark, was the president of Associated Jobbers of Los Angeles. The Association first offered the case to Henry Stephens, and I, for some reason, I don’t remember--disqualification or some inconsistent representation--he didn’t want to take the case. He suggested that they come to Ed Kuster and me, or else my uncle suggested us. I don’t know.

THE PARTNERSHIP OF LOEB AND LOEB

DAVIES: When did you leave Kuster out and become Loeb and Loeb?

LOEB: Ed Kuster left the company shortly after these cases. A long time afterwards, he came up to my office and told me that he didn’t like the ordinary general practice of law. He said that he liked trial law because he was an “exhibitionist.” I had never before heard the term, it was so new in our vocabulary. He explained it to me and said that he liked to perform in court before a judge or a jury. So he preferred to specialize in trying cases. And this is consistent--he moved to Carmel and gave up law completely to establish the Theater of the Golden Bough, which was a combination of the theater and a school of acting.

DAVIES: Then was the partnership Loeb and Loeb?

LOEB: Then Edwin and I went into partnership as Loeb and Loeb. We had offices right next to Ed Kuster--this was all by agreement. He kept the old reception room and one or two others, and Edwin and I had rooms just alongside. Ed Kuster’s wife, Una, married the poet Robinson Jeffers after she was divorced from Ed. When Ed moved up to Carmel, Ed and his new wife built a house on one side of the road, and Jeffers and Una built a house on the other side of the road. They were all very friendly.

DAVIES: How did you get into the motion picture cases, Joe? You used to do a big motion picture business.

LOEB: This is another one of those experiences that show you how much life depends on accident. There was a producer named David Horsely, who had a motion picture studio at Washington and Main Streets on property that been a ball [Ends abruptly in original. –Ed.]

There was a firm of lawyers, both of whom have been dead for many years, who were very careless about their litigation. They would let judgment be taken by default against their clients. They had two default judgments entered against Horsley, and he decided that he should change lawyers. He wrote to his New York lawyer and asked him if he could give him the name of a lawyer in Los Angeles to whom he should go. The New York lawyers wrote to Jesse Steinhart, a San Francisco lawyer whom Edwin and I had both come to know very well. He had graduated from the University before I went there, but through Marco Newmark and in one way or another, we had gotten very friendly with Jesse. So Jesse wrote to the New York lawyer recommending us, and the New York lawyer suggested that the producer come to us.

Here’s the funny part of it. One of the first things he brought to us was an awful row he was having with two brothers who owned a motion picture company where they made what were known as “L-Ko Comedies.” My brother, Edwin, handled the row. Edwin made such a good arrangement for David Horsely that he was tickled to death. One of these brothers said to Edwin, “Why you dirty little so-and-so, the way you treated us is terrible, and if we ever need a lawyer, we are coming to you.” Believe it or not, he did.

Then the two of them kept saying to Edwin, “We want you to meet our brother-in-law.” And Edwin would come to me and say, “What shall I do? These boys want me to meet their brother-in-law. I’ve had trouble enough with them.” Finally, one day Edwin said to them, “Who is your brother-in-law?” They said, “He’s Carl Laemmle, the president of Universal Pictures,” and so Edwin decided that he would meet the brother-in-law. So through the lawyers who let defaults be taken against their client, David Horsely, who wrote to his New York lawyer, who wrote Jesse Steinhart, who wrote back to New York, and because we handled the case for David Horsely against the brothers-in-law of Carl Laemmle, we got into the motion picture business. You know, one of the two brothers is given credit for having said, “L-Ko Comedies are not to be laughed at.”

DAVIES: Then were you lawyers for Universal?

LOEB: We were lawyers for Universal for years.

DAVIES: Then didn’t you have something to do with MGM?

LOEB: Still do.

A. LOEB: You worked for Sam Goldwyn.

LOEB: We did work for Sam Goldwyn, yes.

DAVIES: How did you get connected with him?

LOEB: I really don’t remember, except that we represented a number of motion picture studios at the time, and maybe he came for that reason. I don’t recall whether this was it or whether some lawyers he had used in the east had recommended us.

DAVIES: Can you tell us about any interesting motion picture cases of the early day.

LOEB: Here is a story about Marion Davies and Pomona College. There was a fellow whom we knew very well in college, Walter de Leon, who was in the class of 1906. He became a writer and an actor. He married the sister-in-law of Ferris Hartman. They were on the vaudeville stage for a long time as de Leon and Davis. When he was in college, Walter had written a class play called The Campus. He got to be a professional writer, and The Campus was made into a motion picture produced by one of the studios. Marion Davies was playing the lead in it, and they made the picture on the campus of Pomona College. The Sycamore Inn was a hotel then with rooms for guests. The whole hotel was leased for the leading members of the company for the period of production. A matter came up in which the lawyer for Marion Davies was disqualified, and he called us in to represent her in that matter. He and I came out to discuss the matter with her. That was my first visit to this area, and the first time I saw the Sycamore Inn. When the shooting of the production was over, Marion Davies wanted to show her appreciation of what the students had done because so many of them had served as extras.

A. LOEB: She asked them if they would like a party, and, of course, they wanted a party. I know this because Joe brought me out to the party. The party was held in the Pomona College gymnasium, and Mr. Hearst engaged two orchestras so that they could play longer. One orchestra was a dance orchestra, and the other one was for game-playing, snap-the-whip, musical chairs, and that sort of thing. Marion Davies played in everything that there was to play.

Joe and I first went to the Sycamore Inn because we had not been told that the party would be held on the campus. So we had to go back there. We went into the dance, and Mr. Hearst and I sat on the sidelines while Marion and Joe sat elsewhere discussing the legal problem. I thought that the following was an interesting sidelight on Mr. Hearst. He had just offered a big prize for the first airplane that flew from San Francisco to Honolulu. When he had been in San Francisco the day before looking the planes over, he was distressed because of their poor condition. Some of them were put together with bailing wire and rope. So he was not really in a very happy mood for fear that there would be disasters on the way over. And I think there were, if I remember correctly.

LOEB: Obviously, there was not government supervision of any kind then, and the contestants had the trashiest privately-owned, open-cockpit planes.

DOUGLASS: Continue about the party in the Pomona College gymnasium.

A. LOEB: We watched the dancing for awhile. They played musical chairs, and Marion Davies stayed right in until the end with one of the boys. Then he sat in one chair remaining, and she sat on his lap, trying to get into the chair. Of course, everybody was thrilled about it. It was a wonderful party.

DOUGLASS: When would this have been?

LOEB: It was after World War I--sometime between then and 1921.

DAVIES: Did you ever represent her afterwards?

LOEB: No. Alex Sokolow was her regular lawyer. He obviously would have represented her in any matter, except the one in which he was disqualified. Law is a funny business, you know. Two men can have a fight and shoot each other and call in the same surgeon, and he can treat them both. But if they go to the same lawyer, he can’t take the case.

DAVIES: Did you remember any of these other old firms, like Famous Players, Lasky, Keystone Comedies, Mack Sennett, or Hal Roach, whom you represented?

LOEB: We didn’t represent Mack Sennett or Hal Roach ever. There was awhile when we represented United Artists--Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and someone else. I remember attending one conference when Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks and others were there.

DOUGLASS: Did you particularly enjoy this phase of your practice?

LOEB: No. It wasn’t interesting to me particularly. Some of them are very temperamental, and some of them are very lovely.

DAVIES: Didn’t you represent Loews Incorporated?

LOEB: Didn’t that turn into MGM? Don’t take that for granted because I am a little mixed, but it seems to me that there was a connection between them.

DAVIES: Was the bulk of your practice in motion pictures, or was it in corporation law in general?

LOEB: It was pretty general.

A. LOEB: There were Constance and Norma Talmadge. Because you certainly did a job for Constance Talmadge, I remember. We took her to Riverside.

LOEB: I know that for some reason, somebody didn’t want to be served with process in a federal case, and we drove her to Riverside and put her on a train to the east.

A. LOEB: Then we stayed overnight at the [Riverside] Inn. Dick Bartholomew, who had come with us, had the next room, and in the middle of the night, he had a nightmare. In the morning, we came back to Los Angeles, and went on to see Constance’s mother, Peg. As I walked up the stairs of the house while Joe was parking, a nice man came up to me and said, “Miss Talmadge, I serve you with these papers.” And I said, “But I am not Miss Talmadge.” He said, “Please don’t deny it. Here you are on the steps of your mother’s house.” Joe came up to us and said, “No. This is my wife. This is not Miss Talmadge.” We had quite a time.

LOEB: You asked me about interesting cases. One of the most interesting cases I shouldn’t tell you about, because maybe some of the people who were involved in it are still living and would sue me for slander; and I would have to prove the truth of my statement. The truth can be proven, I am sure, by the court records and maybe by the records in my own office or in Oscar Lawler’s office.

This was after the first World War, and there were a lot of surplus army supplies that had to be disposed of by auction. The government had decided that it would select its auctioneers by trying out various people in various districts and then would appoint a man as its auctioneer to handle all of the auctions in a certain district. They employed a man in Los Angeles. He and three others, three brothers, owned a department store and were clients of ours. This man who was engaged to conduct an auction sale of surplus army goods down towards San Diego held the auction. They held the auction, and then all of a sudden, against the advice of the United States Attorney here, the federal grand jury indicted him and two army officers and some others with fraud in conducting the auction. They claimed that as a result of a conspiracy, the auctioneer had knocked down goods to lower bidders and disregarded high bids.

This was before the day of the FBI. A Secret Service man had been sent to San Diego before the auction because someone had tipped off to somebody in the government that there would be fraud in the auction. The Secret Service man gave the room clerk in the hotel in San Diego five dollars to let him and his young assistant put a dictaphone, and inter-communicating system, between the room that some of these men were going to occupy and the room that the Secret Service men had. He listed in on conversations.

The point is that this Secret Service man completely fabricated a whole story--how he had listened, how he heard John Smith say this and then Bill Jones say that. The government refused repeated requests of the defendants to bring to the trial a number of witnesses designated by them, which defendants in criminal cases are entitled to have done at government expense. As a result, the defendants, at their own expense, had to bring witnesses from all over the country to disprove what was said. When the case was first offered to us, we wouldn’t take it because we hadn’t had any experience in criminal law. But the four defendants insisted, and we agreed to represent them if they would authorize us to employ Oscar Lawler. He had been the United States Attorney here and had handled many criminal cases. We were fortunately able to associate him in the defense.

We proved, for example, that when the Secret Service man said, “And then turned on the phonograph and played so-and-so,” he was hearing a loud speaker from a motion picture theater across the street and that it was utterly impossible to distinguish voices with the intercommunicating systems they had then. Worse than that, this was a paddle auction. Anyone who wanted to bid at the auction had to deposit $3,000 and would get a paddle with a number on it. Then if something was offered for sale, the person had to hold the paddle in the air if he wanted to bid. If the bidding reached a price at which he wanted to drop out, he would drop his arm. His bid would be recognized only if his paddle was still up. We produced witness after witness, brought in at the expense of the defendant because this government man wouldn’t listen to our demands for subpoenas to bring them in, who testified on the stand that he did not have his paddle in the air, but had dropped it, or even in some cases that he did not have a paddle and was not entitled to bid. This was a complete refutation of the prosecution’s claim that the witness had made the highest bid and the auctioneer had ignored his bid and knocked down the article to someone else. It was one of the rottenest cases you can imagine. It was just cooked up.

Harding, at the time president of the United States, had sent a special prosecutor to handle the case. When it came to the argument to the jury, the special prosecutor was defending himself and the Secret Service man, trying to excuse both of them for what they had done, rather than to make a case against the defendant. The jury stayed out about an hour and twenty minutes and came out with a verdict of “not guilty” for every defendant. I said to one of the jurors, “Why did you keep us waiting so long?” “Well,” he said, “there wasn’t a minute when any one of us would have voted any other way, but we sort of felt that since the government sent out a special prosecutor and the case has been tried for six weeks, it wouldn’t look right if we didn’t stay out at least that long.”

DOUGLASS: Is there a record of the case?

LOEB: It wasn’t reported. There wasn’t any appeal.

THE HELLMAN FAMILY

DAVIES: How did the Hellman family become such big-time bankers? When I first came here in the early twenties, there were Hellman banks everywhere.

LOEB: One of the Hellmans and one of the Meybergs owned property of which the western section of this little grove in Alta Loma [where the interview was conducted] was a part. Two streets over, the street is called Hellman Avenue, because Hellman owned a lot of land around here. I don’t know where they came from originally or when.* I. W. Hellman was the financial genius of that family, and he established the Farmers and Merchants National Bank. Later, Herman Hellman left the Farmers and Merchants Bank and established another bank, called the Hellman Commercial Trust and Savings Bank, I think. When things got pretty bad during the Depression, the Hellman Bank was merged with the Bank of America.

Irving H. Hellman, a son of Herman Hellman, and I sort of grew up together. He was about my age, or maybe a year older. His older brother, Marco, is the one who took over the family investments and got them into financial difficulties.

DAVIES: Did all of the banks collapse?

LOEB: That Hellman Bank would have collapsed during the days when there were raids on banks. My recollection is that they were in trouble and there would have been a run, or there was a run, on it, but I think that the Bank of America took them in. There were an awful lot of Hellmans, and I don’t know the relationships. I. W. Hellman was the big, original, successful financier, and he moved to San Francisco and stayed successful. Then they put his brother, Herman Hellman, in charge of the Farmers and Merchants Bank here.

A. LOEB: When Rita Levis married Marco Hellman, they were very wealthy. That’s when I came down here to the wedding. Rita Levis was a Stanford girl who came from Visalia.

LOEB: Then there was a Maurice Hellman who was an officer of the Security Bank. There was a James Hellman who was a hardware merchant.

A. LOEB: It was the younger one, the son, who ran into trouble with the bank. Marco was the one.

LOEB: Irving was never a banker. Unless my memory is at fault, he never worked in either of the banks. Irving Hellman was employed by the contractor who built the old Philharmonic Auditorium. I don’t remember that Irving ever went into banking. But Marco did. He made a lot of commitments and did a lot of things that weren’t too good in their results.

DOUGLASS: All during this period, where were your law offices located?

LOEB: We were in different places. We started out in the I. W. Hellman Building at Fourth and Main Streets. Then we moved to the Haas Building at Seventh and Broadway, and from there, up to Pacific Mutual Building, where we still are. We were almost the first tenants to move into that building. We moved there in 1921, and the building wasn’t quite finished.

DAVIES: Did the Pacific Mutual Insurance Company go bankrupt at once?

LOEB: No. It went through a reorganization. Irving Walker was still with us then. Allan Balch was chairman of a Pacific Mutual stockholder’s committee that didn’t like the plan of reorganization that had been put over rather hurriedly with the approval of the Superintendent of Banks. So we were retained by the stockholder’s committee to upset that plan and get in something better. The Pacific Mutual never was bankrupt, though. It went through the equivalent of receivership, I suppose. I don’t know if there ever was a receivership. I don’t think the management was ever taken away from them.

They had a policy called a non-cancellable health policy. You paid a certain sum of money, and the company could never cancel the policy. If you were disabled for ninety days, it would pay $1,000 a month, if that was the amount of your policy, or maybe they were all $1,000, as long as you were disabled. It was just utterly impossible to keep solvent and keep on selling those policies. That brought about the crisis which resulted in the reorganization. But they never did go broke in the sense that their outstanding life policies were cancelled.

MEMBER OF THE CALIFORNIA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION

DOUGLASS: Tell us about your appointment to the California Board of Education.

LOEB: I was appointed by Earl Warren in 1943, and then he reappointed me. I served until 1956. Goodwin Knight didn’t reappoint me.

DOUGLASS: Why were you appointed, do you think?

LOEB: I never quite knew. I was sitting at my desk one day and the telephone rang. Somebody said that Governor Warren was calling me from Sacramento, and I thought, “Good heavens, what have I done?” He said, “Joe, I want to appoint you to the State Board of Education.” I asked some questions about it. To be honest, I had never heard of the State Board of Education. He explained very carefully that I would get no salary. I said that I would have to talk to my partners, as I didn’t know how much time it would take, and it would mean that I would have to take time away from my work. Then when I got through, I said to myself, “Well, after all, it is sort of a draft to get into public service, and so I will say ‘Yes.”’ And then I rushed into the library to find out what the State Board of Education was. That’s how qualified I was to act.

The State Board of Education at that time administered all the public schools of all levels in the state, except for the University of California, which is a public trust. In recent years, a committee, including my good friend Arthur Coons as chairman, split off the state colleges from the rest of the schools with a separate board. So I suppose the next thing will be to split the high schools from the grammar schools, et cetera, and there will be separate boards for everything before they get through.

DOUGLASS: Did you know Earl Warren as a lawyer?

LOEB: I knew Warren first of all as an officer of the Alumni Association of the University of California. I met him at one or two meetings. We never had, as far as I can remember, any personal contact as lawyers. I did know him personally. Although he never told me, I always felt that my name was suggested to him by Jesse Steinhart, the San Francisco lawyer whom I mentioned before.

DOUGLASS: Were you on the Board of Education when the Report, the Master Plan for Higher Education, was done? That was 1946-47. My father-in-law, Aubrey Douglass, completed the Strayer Report (1948).

LOEB: Yes. If you will look in the material accompanying the Strayer Report, you will find a proposed constitutional amendment that would provide for the appointment by the Governor of the members of the State Board of Education, subject to confirmation by the Senate, and the only thing that the State Board member would have to do by way of election would be that at the end of his term, his name would go on the ballot, just like justices of the Supreme Court, “shall be re-elected.” (See Printed Report of February 1945, typed, Appendix I, p. 15.) He wouldn’t have to campaign against anybody. The State Board of Education would appoint the State Superintendent, and he wouldn’t have to run for election. The State Board would fix his salary.

These were and are my views on the subject. I drafted the amendment. In fact, George Strayer used to refer to it as the “Loeb Amendment” in front of the Board, and we were for it. I remember that the Superintendent of Schools, then Walter Dexter, said, “I am for this--lock, stock, and barrel.” It got into the legislature, and then the legislature began, just as they are doing now, to work on it. One of the first things that they did was to try to amend it so that the state would be divided into districts and members of the State Board of Education would be appointed to represent districts. We never felt that we were representing districts. We thought we were representing the people of the State of California, and I still think that’s what the Board ought to do.

DOUGLASS: You are for an appointed Board and an appointed Superintendent, then?

LOEB: Yes. I worked out that amendment over the weekdays in the law office of the late Charles De Young Elkus, Amy’s uncle, in San Francisco, where there were books with pertinent statutes and other material. If you compare the provision of the amendment that we proposed with the provisions of law relating to the Justices of the Supreme Court, you will find that they are pretty similar.

DOUGLASS: Then you disagree with Mr. [Max] Rafferty, who wants an elected Board?

LOEB: Yes, definitely. In fact, I didn’t even vote for Mr. Rafferty.

DOUGLASS: The Strayer Report has become such a landmark. you remember why you as a Board felt moved to have the report done? James Conant, in his book, refers to California’s advanced master planning in higher education as a model. Do you recall why it was done?

LOEB: I don’t remember who started the movement to have Strayer make the Report. The other day I had the Report out, and I was reminded of something that I had forgotten. The Report was not directed to the State Board of Education. It was directed to a commission or a committee. Whether the movement to engage Strayer to make that study originated in the Board or outside, I don’t know. I have no recollection that we started it. I remember meeting Strayer and having him appear before the Board.

I think that having an elected Board would be too bad. Would you tell me what decent citizen is going to come out and campaign to be elected to the State Board of Education if he has to run in opposition to somebody who is supported, let’s say, by the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, or some other powerful and wealthy organization? Why would I waste my time, my money, or ask my friends to put up campaign funds to have me elected against Dave [referring to David Davies], if Dave is running against me. Dave would say what a terrible person I am--he doesn’t even know how to spell. Then I would have to say that Dave knows how to spell but he knows how to spell wrong. How could you expect decent, respectable people to go into that? That’s my view of it.

LOEB: Do you know that there isn’t one single requirement in the law of what the Superintendent of Schools must be--his qualifications. He doesn’t even have to pass an examination like the Negro voters do in Mississippi. He doesn’t have to prove he can read. All he has to do is get his name on the ballot.

Then another thing that I don’t like about the Coons Report on Higher Education is that the theory is wrong. Our theory was, and it was the theory we inherited, that the public schools, aside from the University, with which it cannot interfere because it is provided for in the Constitution as a trust (the legislature can’t monkey with it, although it can do an awful lot by refusing money), in California should be kept on some kind of consistent basis. There should be a central body to govern and control. For example, the way it is now with the state colleges separate from the rest of the schools, the state colleges can require, let’s say, the teaching of Sanskrit as a condition of admission to a state college, but the State Board of Education may say, “We’re not going to have the children in our public schools have to learn Sanskrit.” There’s no necessary consistency.

DOUGLASS: What do you remember of your reactions when you first began working on the Board?

LOEB: If my recollection is correct, at my first meeting there was a letter signed by six or more married couples who were protesting that the schools didn’t teach spelling. I don’t know why I did it, but when Walter Dexter finished reading the letter, I asked him to let me read the letter. I found six mistakes in spelling in that one letter.

DOUGLASS: You were on the Board when Roy Simpson was appointed State Superintendent, weren’t you?

LOEB: Dexter suddenly died at his desk, I believe. Simpson was appointed by the Governor.

A. LOEB: He was appointed, but you all liked him right away. That was such a good board.

LOEB: She’s bragging about people on the Board like Barney Atkinson from UCLA and [William L.] Bill Blair of the Pasadena Star News. We three lived in Los Angeles and Pasadena. Had the state been redistricted, according to at least one bill that is pending before the state legislature now and one of the proposed changes amendments that our Board offered, it wouldn’t have been possible for the three of us to be on the Board. Two of us would have been disqualified because we would have been in the wrong district. Blair was president of the Board.

The Board handled the approval of textbooks. One of the matters with which our Board dealt was the consideration of the Building America series as supplementary reading. We had to appear before the Senate Committee on Education because a Palo Alto lawyer and the president of some war veterans’ organization, I think, filed a complaint with the state legislature charging State Superintendent Roy Simpson, the State Board of Education, Professor Jaffe of Stanford (who at that time was in Europe on a governmental mission helping to re-establish public education in the schools of Germany after the war), and the National Education Association with being parties to a Communist conspiracy to deliver the schools to communism.

Senator Jack Tenney was not on the committee, but was present as a guest at the hearings. He sat up on the stage, and he began to take over so much that the senator who was the chairman of the committee said, “Senator Tenney, I want to remind you that you are not presiding over this meeting. You are here as a guest of the committee. I am the chairman.” We had to stand up there and defend ourselves against the charge that we were Communists.

The session adjourned, and my wife and I walked down the corridor to wait for the elevator. Tenney came up, and he put his arms around me and made a curious statement. Before repeating it, I’ll have to explain about one of the pieces of evidence used against us. Some twelve years previously, a schoolteacher up in one of the northern school districts had been fired and his credentials revoked because, not in class but outside of class, he had made subversive remarks with the pupils. He didn’t want the children to salute the flag first thing in the morning. After his discharge, he took his case to the Supreme Court and lost. Some twelve years went by, and this man applied to have his credentials renewed. We had appointed the lawyer for the State Board of Education to be an examiner, to investigate and make a report and recommendation to us. The recommendation was favorable. This man some twelve years before may have said some objectionable things. But during the war he had demonstrated his patriotism. He had worked in one of the shipyards near Vallejo helping build ships for the Navy. At any rate, it was a favorable report and recommendation that we renew the credentials. One of the pieces of evidence introduced at the senate committee hearing to show that we were Communists was that we had voted to restore the credentials of this man.

So Tenney came up to me and said, “Mr. Loeb, I know you’re not a Communist. I know you’re a good citizen. But the trouble is that you don’t understand the Communists. You believed that this man who had once been a Communist had reformed, but you don’t understand them. You don’t know that if you are once a Communist, you never change. You are always a Communist. But you don’t know that, because you never were one. I know it because I was.” Now, you make sense out of that!

A. LOEB: He [Tenney] scared me.

THE RUSSELLS AND THE CUYAMA OIL FIELDS*

LOEB: There was Hubbard Russell, his brother Joe, and a third brother, Harvey. Their father was a cattle raiser. The family lived on a ranch near Oxnard. When the parents were still living, I used to go up there when I was still in high school. After they died, Amy and I used to go up there with our own kids and have picnics with the Russells down the stream a little way from the ranch. The Russells were cattle raisers, and that’s the only business in which they were trained.

So one day a man showed up at the Russell Ranch, and he said he was there representing a San Francisco bank which had had to foreclose on a large ranch, and under the state law could only hold that ranch a certain length of time, because under state law, a bank cannot own land except for banking purposes beyond a certain length of time. And so the bank had to get rid of this land. He said, “It would be a wonderful place for you people because it’s green all the year around. You will be able to pasture your herds on that land. You won’t have to be renting land down there in San Diego County or Arizona and transporting your cattle. You can feed them on this ranch, and it will only cost you so much.” He named an amount that seemed fantastic to the Russell boys. They said, “We’re not in the real estate business. We have been trained as cattle raisers, and we’re not going to get ourselves involved.”

So the fellow went away and came back some time later. He said, “The bank must get rid of the land. The time is almost out.” Instead of the price he had named before, he named a much lower price, but specified that the bank would reserve the mineral rights. And the Russell boys said, No. What does that mean. We buy this land. We’re running cattle on it. Along comes somebody who says, ‘I own the mineral rights, and I’m going to put in wells and do this and that--your cattle are in the way. So get them off.”’ So the fellow disappears, and he comes back a third time. He says, “Listen, the bank will let you have the land at this very low price and the mineral rights can go with it. They’ll say nothing about the mineral rights.” So the Russells made the deal. They had a place to graze their cattle.

After awhile, a man came along--somebody whom they knew and who had had an awful time making a living. He used to get property owners to enter into oil leases, and then he would go to the oil companies and ask them to buy the lease from him. The Russell boys were so sorry for him that when he showed up and asked them if they would give him a lease on this ranch they had bought, they said, “Sure.” So he goes to the oil companies and sells the lease. Some wells were drilled, and that started the Cuyama Oil Fields. The Russell brothers now get their royalties from all the oil that has been developed from that land.

HARRIS NEWMARK SELLS SANTA ANITA RANCH TO LUCKY BALDWIN

LOEB: One of my favorite stories along the same line is about how my grandfather, Harris Newmark, sold the Santa Anita Ranch to Lucky Baldwin. My grandfather owned that land and used to run sheep and cattle on it. One day a man named Baldwin came to him and said, “Harris, I’d like to buy your ranch.” My grandfather named a price ($150,000 approximately), and Lucky Baldwin said, “No. That’s too much.” He went away. He came back some time later, and he said, “Harris, I’m willing to buy your ranch at that price.” My grandfather said, “Lucky, you’ve waited too long. I’ve raised the price $10,000 (or whatever it was).”

And that went on until I think my grandfather asked $190,000 for the whole darned Santa Anita Ranch. Lucky said, “Harris, that’s too much. I won’t pay $190,000.” My figures may be wrong, but the point remains. Lucky showed up again, and my grandfather didn’t notice that he had a valise in his hand. He said, “Harris, I’m willing to pay you $190,000.” My grandfather said, “You wait too long. My price is now $200,000.” So Lucky lifts the valise upon the desk or counter, and say, “Harris, here’s your money.” And he got the whole Lucky Baldwin ranch for something like $200,000. [This was in 1875.]

DOUGLASS: How did your grandfather happen to own the area?

A. LOEB: I guess he got it for good cattle land.

LOEB: He bought it around 1873 from Louis Wolfskill. In those days, land cost practically nothing. If you read the life of L. J. Rose, you will find that L. J. Rose bought Rosemead at something like fifty cents an acre.

Then one day not long after I was admitted to practice, a man named Robert Marsh, who had been a prominent real estate dealer in Los Angeles, and an agent came up to my office.

LOEB: They said, “Joe, your grandfather and a couple of his relatives own some hill land near Montebello, and we agreed to buy it for $100,000. We paid $40,000 in cash and gave them a mortgage for $60,000. The mortgage is coming due pretty soon, and we can’t meet it. Would you get an extension of time from your grandfather?”

So I told my grandfather that Robert Marsh wanted an extension of time. My grandfather said, “Why shouldn’t I give them an extension of time? What do I want with all that dry land? I don’t want to run sheep on it anymore. There’s no water. What could I do with it?” So he gave them the extension of time. In due course, Robert Marsh sold his rights to someone else, and the mortgage was paid off. Somebody drilled some oil well on that unwanted hill that is now known as the Montebello Hills.

INDEX

Baldwin, E. J. “Lucky,” 22-23

City of Paris Store 1, 2

Cohn, Kaspare 2, 3

Davies, Marion 11, 12

de Leon, Walter 11

Getz, Milton 2

Goldwyn, Sam 11

Hearst, William Randolph 11, 12

Hellman, Irving 15, 19

Hellman, Marco 15, 16, 19

Horsely, David 10

Kuster, Edward G. 7, 8, 9

Laemmle, Carl 10

Lawler, Oscar J. 13, 14

Loeb, Edwin 7, 8, 9, 10

Loeb, Leon 1

Meyer, Ben R. 2

Meyer, Eugene, Sr. 3

Newmark, Harris 1, 2, 22, 23

Newmark, Marco 1, 2, 4-6, 15

O’Melveny, Henry W. 3, 5, 6, 7

Russell, Hubbard 21-22

Stephens, Henry J. 7, 9

Strayer Report on Higher Education 18, 19

Talmadge, Constance 13

Tenney, Senator Jack 20, 21

Walker, Irving 6, 16

Warren, Earl 17

INTERVIEW AGREEMENT i

INTERVIEW HISTORY iii

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH iii

FAMILY BACKGROUND 1

LEGAL TRAINING 4

IN PRACTICE AS KUSTER, LOEB AND LOEB 7

THE PARTNERSHIP OF LOEB AND LOEB 9

THE HELLMAN FAMILY 15

MEMBER OF THE CALIFORNIA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION 17

THE RUSSELLS AND THE CUYAMA OIL FIELDS 22

HARRIS NEWMARK SELLS SANTA ANITA RANCH TO LUCKY BALDWIN 23

INDEX 25

Memberships and Activities of Joseph P. Loeb

1. Board of Directors of Los Angeles County Bar Association: 1915-1922

2. Chairman of Bar Association Grievance Committee: 1915

3. Committee of Community Chest: 1932-1947

4. State Board of Education: 1943-1955

5. President of Hillcrest Country Club: 1933-1937

6. Director of Los Angeles Tuberculosis and Health Association: 1940-1946

7. Director of Federation of Jewish Welfare Funds of Los Angeles: 1944

8. President of United Jewish Welfare Fund: 1937; and General Campaign Chairman: 1938

9. Board of Directors of the Los Angeles Branch of the Indian Defense Association

10. Board of Governors of Town Hall: 1944-1947

11. Advisory Board of American Council for Judaism and Vice President of its Philanthropic Fund

12. Board of Directors of Welfare Federation of Los Angeles Area: 1949

13. Board of Fellows of Claremont University Center

14. Life Member of Independent Order of B’nai B’rith, Los Angeles Chapter

15. University of California Alumni Association

16. Affiliates of UCLA

17. Friends of UCLA Library

18. Boalt Hall Alumni Association

19. Founding Friends of Harvey Mudd College

20. Friends of Claremont Colleges

21. Founder Member, Los Amigos del Pueblo: 1969

22. Honnold Library Society